Image: NASA/GSFC

The plume of hot rock that sits beneath Iceland has long-reaching fingers – two of which stretch all the way to Scotland and Norway. This could help explain why the Scottish Highlands aren’t submerged beneath the waves.

Mantle plumes are like chimneys that transport hot, buoyant rock from deep inside Earth. When they break through to the surface, the volcanic activity they generate can fuel the formation of islands, such as the Hawaiian archipelago.

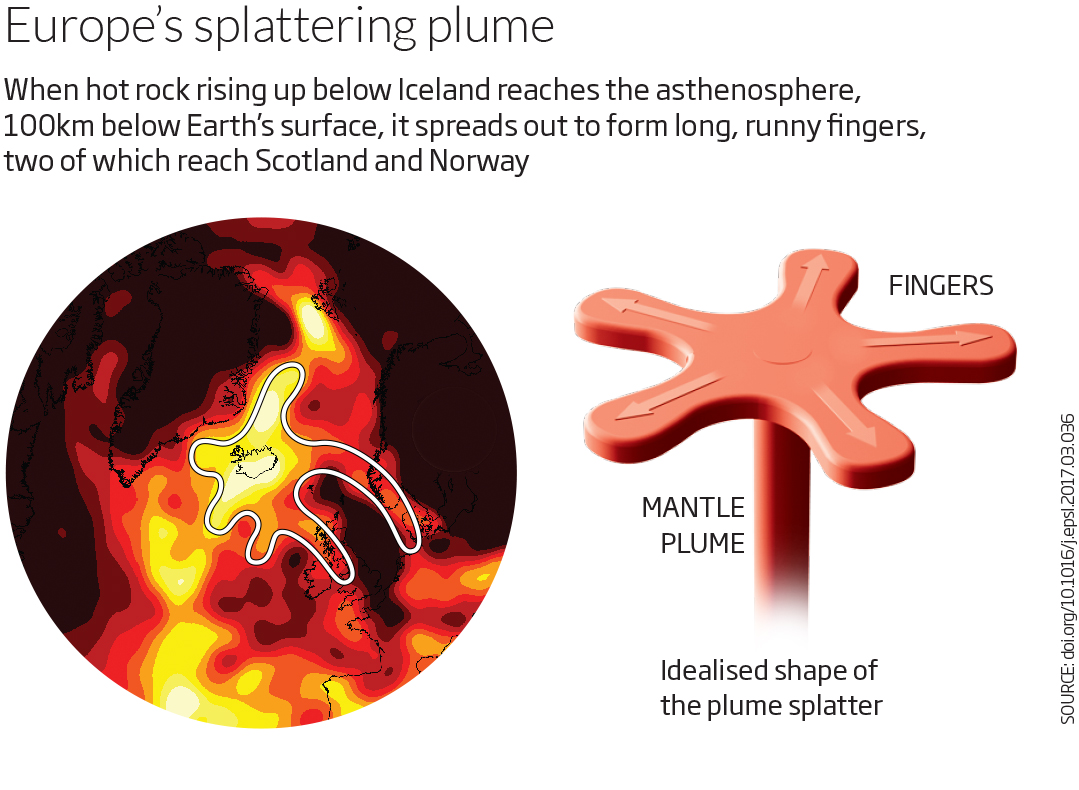

Iceland also owes its existence to a mantle plume – and seismic maps of Earth’s interior suggest that this plume doesn’t have the typical circular outline. In fact, it looks a bit like flower petals or a star shape on top of a chimney of rising hot rock. But why or how that irregularity arises has remained a mystery until now.

When Nicky White at the University of Cambridge saw one particular map of the plume’s outline below Earth’s surface, he realised how it might have gained its irregular shape. Colleagues of his in Cambridge have looked at how fluids with different viscosities mix in the confined, almost two-dimensional, gap between two stacked sheets of rigid material such as glass. These experiments show that when a runnier fluid is squirted into a more viscous one, it forms an intricate radial pattern of branches, or fingers.

White and his doctoral student Charlotte Schoonman think the plume is behaving just like the fluids in the lab experiments, but on a much grander scale. About 100 kilometres below Earth’s surface lies a layer called the asthenosphere, a zone of relatively free-flowing rock held between two horizontal layers of stiffer rock. The idea is that the Iceland plume injects hot, runny rock into this layer – and that this spreads out horizontally through the asthenosphere, forming fingers. Other plumes don’t form such tendrils, says White, because the rock within them is not sufficiently hot and runny, or injected with enough force. In lab experiments, fingers form a nice radial pattern. The fingers in the Iceland plume are much more asymmetrical, probably because the rigid crust beneath nearby Greenland is so thick that it acts as a barrier, reducing finger formation on the western side of the plume.

The fingers on the plume’s eastern side seem to stretch surprisingly far, one reaching Scotland, some 1000 km away, and another one reaching even further, to Norway. The hot fingers may even help to explain why Scotland and western Norway lie above sea level.

Earth’s crust beneath these areas is unusually thin, meaning that both regions should in theory be below sea level. “Something else must be going on to explain why they’re not under water,” says White. “And that something else is the hot fingers.” This is because the hot rock is relatively buoyant, which could compensate for the thinness of the crust, pushing it up.

The idea that Iceland’s plume is influencing the geography of north-west Europe isn’t new, says White, but exactly how it does so has been unclear. The “hot finger” model provides an explanation. Taras Gerya at the Swiss Federal Institute of Technology in Zurich thinks that the model makes sense. “It seems realistic to me,” he says.

This story is based on an article in New Scientist. The original paper was published in Earth and Planetary Science Letters.

Bill Gray