Animals may have evolved 350 million years earlier than previously thought. Fossils that seem to be sponges, one of the first groups of animals to evolve, have been found in rocks formed 890 million years ago. Elizabeth Turner at Laurentian University in Sudbury, Canada, made the discovery.

Animals are mostly multicellular organisms whose bodies are made up of distinct tissues, and unlike plants they have to eat food to survive. For years, the earliest-known animal fossils were from the Cambrian Period, which began 541 million years ago. However, in recent years, some fossils from the earlier Ediacaran Period (635 to 541 million years ago) have been identified as animals. There are also 660-million-year-old chemical traces that may be from sponges.

Turner studied rocks from north-west Canada that contained the preserved remains of reefs from 890 million years ago, during the Tonian period. These reefs weren’t made by corals, like modern reefs, as these didn’t exist at that time. Instead, they were made by photosynthetic bacteria living in shallow seas. The reefs, known as stromatolites, were many kilometres across and rose to heights of hundreds of metres above the seafloor. Within the rocks, Turner found the preserved remains of a network of fibres, which branched and joined up in a complex mesh. These are the remains of sponges, she argues, but “not a normal fossil”.

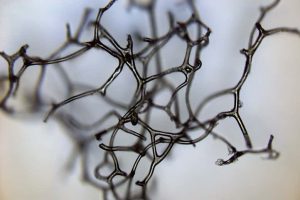

The bodies of modern sponges contain a mesh made of a protein called spongin, which forms a soft skeleton. Turner’s work suggests that when ancient sponges died, their soft tissues became mineralised, but the tough spongin didn’t. Eventually, though, it decayed, leaving hollow tubes within the rock that later filled with calcite crystals. These networks of calcite (pictured above) are what Turner then found – and the way the network branched looked just like spongin (pictured below).

The spongin skeleton of a modern sponge (E.C. Turner)

Similar fossils from later periods have been convincingly identified as sponges, says Joachim Reitner at the University of Göttingen in Germany, who has studied preserved sponges. “We have no other organisms forming this type of network in this way.”

If sponges existed 890 million years ago, then animals must have originated much earlier than previous fossils have suggested. “Molecular clock” studies that use modern DNA to estimate when key points of evolution occurred have indicated that animals emerged long before the earliest fossils. However, this approach is often thought to be less reliable when there aren’t any fossils available to calibrate the molecular clock. Turner’s finding “brings the fossil record back into line with the molecular clock estimates”, says Amelia Penny of the University of St Andrews.

However, an earlier origin of animals changes two key aspects of their story on Earth. First, there was little oxygen in the air until levels rose between 800 and 540 million years ago. This rise in oxygen is thought to have enabled the evolution of animals, but if animals already existed 890 million years ago, it suggests that the first and simplest animals could survive with little oxygen, says Turner. In line with this, Reitner says that many modern sponges can tolerate low-oxygen conditions.

Second, most of the planet froze over in the period between 720 and 635 million years ago, becoming a “snowball Earth”. “It’s previously been thought these are really catastrophic events for life on Earth, certainly multicellular life,” says Penny. But it seems sponges, at least, survived the glaciations.

Finally, there is the question of which animal group was the first to emerge. Palaeontologists have generally assumed that sponges were first, but in the past decade some genetic studies have suggested that comb jellies – which superficially look like jellyfish – actually preceded them. Penny says that finding early sponges doesn’t mean there weren’t also early comb jellies, because such soft-bodied animals are rarely preserved.

This story is based on an article in New Scientist. The original research was published in Nature.

Bill Gray